Write your search in the input below and press enter.

Esc to close.

WSJ: Fentanyl’s Ubiquity Inflames America’s Drug Crisis

The synthetic opioid, whether on its own or in tainted heroin, cocaine, Adderall and other drugs, has spread to every corner of the illegal drug market and is driving overdose deaths to records.

Arian Campo-Flores & Jon Kamp

The Wall Street Journal

COLUMBUS, Ohio—Fentanyl, the potent opioid driving U.S. drug deaths to record highs, has infiltrated virtually every channel of the illicit drug supply and turned it more toxic than ever.

In this city and across the U.S., traffickers are making fentanyl, primarily produced in Mexico, the dominant substance for opioid users craving a fix. The synthetic drug is killing users who fear its strength but can’t easily find alternatives, as well as those seeking it out to feed their rising tolerance to prescription painkillers or heroin. It also is claiming the lives of people who didn’t know they were taking it.

“Fentanyl has changed everything,” said Shawn Bain, a Columbus-based drug intelligence officer with the Ohio High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, part of a federal program to assist law enforcement. “It’s just flooded the market.”

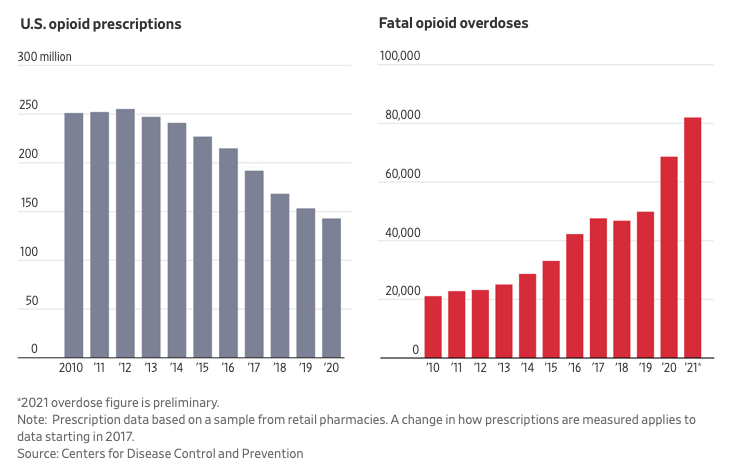

As a result, even though prescriptions in the U.S. outside of hospitals for opioids fell about 44% in the eight years to 2020, opioid overdose deaths nearly tripled in that time span, and moved even higher in 2021. The deaths reached about 82,000 last year, according to preliminary federal data.

Fentanyl is a powerful legal medication, prescribed for cancer patients and others with severe pain. Dealers often sell powder drugs they claim are heroin or cocaine but actually contain an illicit form of fentanyl, which is cheap and easy to make, according to law-enforcement officials. And drug users buying pills that look like painkillers, sedatives or stimulants frequently wind up with counterfeits containing the illicit fentanyl, many of which are stamped out by drug cartels to look identical to the legitimate medicines.

The proportion of seized counterfeit pills in the U.S. containing a potentially lethal dose of fentanyl increased to 44% in 2021 from 10% in 2017, according to samples analyzed by the Drug Enforcement Administration. The agency in April warned law-enforcement departments across the country about an increase in fentanyl-related mass-overdose events involving three or more overdoses around the same time and location, citing instances of people who unknowingly consumed the drug.

Columbus, situated at the intersection of major interstate highways, is a hub for drugs shipped north from Mexico and distributed across the Midwest, Appalachia and the Eastern Seaboard, drug-enforcement officials said. It is the capital of, and largest city in, a state long on the leading edge of the opioid epidemic.

Its dire drug problem is a stark illustration of the epidemic’s trajectory nationwide. After the rampant prescribing of pain pills seeded widespread dependence, restrictions reined in that supply. Heroin and other opioids filled the void. Now, illicit drugs are deadlier than ever because of fentanyl’s pervasiveness and its mixture into a host of substances, law-enforcement officials said.

The number of known opioid users in the U.S. has declined in recent years amid a crackdown on prescription pills, according to federal data. Opioid prescriptions from retail pharmacies fell from a peak of 255 million in 2012 to about 143 million in 2020, the most recent federal data estimate. Purdue Pharma, hobbled by lawsuits alleging sales of its addictive painkiller OxyContin helped fuel the opioid crisis, pleaded guilty in 2020 to federal felonies involving its opioids, and the family who owns the company struck a settlement with states this year as part of continuing bankruptcy proceedings.

The amount of prescription opioids dispensed in Franklin County, which includes Columbus, declined by more than half between 2015 and 2021, according to state data. But overdose deaths in the county roughly tripled over that time to 825 in 2021, a slight decrease from the peak of 859 in 2020, according to county coroner Dr. Anahi Ortiz. Nine in 10 of the deaths last year involved fentanyl.

During finals in May at The Ohio State University in Columbus, two students died off campus after they were exposed to—possibly accidentally ingesting—a powdered drug in a baggie that witness and cellphone evidence suggests they believed was Adderall, a stimulant some students use as a study aid, according to Columbus police.

Toxicology tests showed they died from fentanyl. Evidence indicates they found the drug in a school library and took it to an apartment, the police said.

One of the students, 21-year-old Tiffany Iler, was a pre-med neuroscience major finishing her junior year. She planned to become a physician, marry her boyfriend and raise four children, according to her father, Rich Iler.

“She was poisoned, that’s what it was,” Mr. Iler said. “I want people to know what the hell is going on in this country. This is insane.”

In Ohio, the share of heroin seizures that also contained fentanyl jumped to 81% in 2021 from 4% in 2014, according to crime-lab data compiled by Dennis Cauchon, president of the nonprofit Harm Reduction Ohio, which supports policies aimed at decreasing overdose deaths. The share of cocaine seizures in which fentanyl also was detected increased to 15% from less than 1% over that period.

Tainted drugs are so common in Columbus that the city, like others around the country, has a program to distribute fentanyl testing strips to users so they can determine whether substances are contaminated with the drug.

“Tell me what’s in the drug supply, and I’ll tell you how many people will die,” Mr. Cauchon said, referring to the way fentanyl heightens the risk of fatal overdoses. A study he and other researchers published last year in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence that analyzed Ohio drug-seizure and overdose-death data from 2009 to 2018 found that changes in the composition of the drug supply help predict trends in overdose-death rates.

South of downtown Columbus, a one-story brick building once housed a medical clinic that from 2006 to 2013 was what federal prosecutors described as a “pill mill”—an illegitimate painkiller-prescribing operation. One of many such illegal ventures that operated at the height of the pain-pill wave, it eventually was shut down, and the owner pleaded guilty to drug, tax and fraud charges.

Hundreds of patients a day once visited the building, some lining up early in the morning before packing into a waiting room, said Mike Allen, a retired Columbus narcotics detective who worked on the case. They typically paid cash to get prescriptions for up to 150 pills, he said.

As the pill mill and others like it were shut down, traffickers filled the gap with heroin and then fentanyl, drug-enforcement officials said. When fentanyl first arrived in the city, many users tried to avoid it, fearful of its deadliness. Over time, though, its powerful high prompted some to seek it out.

Two miles up the street from the former pill mill stands a detox facility, Maryhaven Addiction Stabilization Center, that Zach Doyle visited in July to get off fentanyl. He said he had abused opioids for about 20 years, starting with prescription painkillers after he broke some bones in the early 2000s, and later switching to heroin when the pills became too expensive. He got started on fentanyl unintentionally, he said, when dealers began mixing it into heroin.

The drug delivered a rush that hooked him, he said, and posed a greater risk of killing him than any opioid he used before. Three years ago, he overdosed for the first time because of fentanyl. Last year, he overdosed again. The drug has killed more than 20 of his friends.

“Doing any other drug is nothing compared to doing fentanyl,” said Mr. Doyle, 42. “I know if I go back, I’m probably going to die.”

Fentanyl’s infiltration into the supply of cocaine and other stimulants is contributing to a disproportionate increase in overdose deaths among Black people in Franklin County. The share of overdose deaths made up by Black people rose to 29% in 2021 from 21% four years earlier, while the share made up by non-Hispanic white people declined to 65% from 76%, according to the county coroner’s office. The county’s population is 61% non-Hispanic white and 24% Black, census data shows.

The change echoes a nationwide problem. The U.S. fatal overdose rate—or the rate of death per 100,000 people—for the Black population surpassed the rate for white people in 2020, marking the first time this has happened since 1999, federal data show. Researchers say issues such as uneven access to healthcare including effective drug treatment puts Black people at high risk to the increasingly toxic drug supply.

East of downtown Columbus, the treatment center Community for New Direction serves an area with a large Black population ravaged by crack cocaine use in the 1980s and 1990s and more recently by the pain-pill wave, said Chief Executive John Dawson.

“People are still using cocaine and crack, but it’s cut with fentanyl, and then they become addicted to fentanyl, quite often without their knowledge,” he said. Some clients seeking treatment insist they don’t use opioids, he said, yet their urine tests come back positive for the drugs.

The U.S. attorney’s office in Columbus in June said it had made likely the largest-ever fentanyl bust in its district, which covers the southern portion of the state, stemming from an alleged operation to transport drugs to the city by semi truck from Los Angeles. The haul involved more than 70 kilograms of drugs identified as fentanyl, including more than 115,000 pills laced with the opioid, the U.S. attorney’s office said.

“The fentanyl is so strong, you only have to do a little tiny bit of it,” said Courtney Collmar, 35, who is in treatment at a Maryhaven residential facility, one of the organization’s numerous sites in Ohio, after overdosing at least six times on fentanyl, most recently in June. That time, she said, she was sitting in a chair when her friend said she started making strange noises and her face turned blue and her lips purple. Her friend revived her with two doses of naloxone, an opioid-reversal drug, she said.

While bulk shipments of drugs like heroin and cocaine transported into Columbus tend to be free of fentanyl, local dealers often adulterate them with the synthetic opioid, drug-enforcement officials said. Dealers may add it to give drugs an extra kick, or to hook users more intensely, according to the officials. Sometimes, dealers are sloppy—using the same blenders to cut different drugs and inadvertently contaminating them with fentanyl, officials said.

Drug samples seized by law enforcement are increasingly complex mixtures, said Jessica Toms, laboratory manager at the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation. They often contain fentanyl or chemically similar fentanyl analogues such as para-fluorofentanyl, she said. A sample tested in June contained six substances, including fentanyl, para-fluorofentanyl and heroin.

Columbus has responded to the opioid crisis by creating a plan to boost treatment capacity, increase distribution of naloxone, the reversal drug, and track data to identify overdose surges, said city health commissioner Dr. Mysheika Roberts.

Some neighborhoods remain overrun with opioids. West of downtown Columbus, a neighborhood known as the Bottoms because of its vulnerability to river flooding, is rife with dealers and “trap houses,” where users buy and consume drugs, law-enforcement officials said. On many streets, withered people amble past boarded-up storefronts and dilapidated homes.

Sherry Glassnap, 47, who grew up in the area, said she began using pain pills in her late 20s when a doctor prescribed them following ovarian surgery. After the crackdown on prescriptions, she said heroin and later fentanyl invaded the street where she lived in the mid-2010s. When she bought illicit pills, she said she knew they could be tainted with fentanyl but used them anyway to stave off withdrawal.

“You roll the dice,” Ms. Glassnap said.

Her sister died of an overdose in 2018 after ingesting what she thought was cocaine but turned out to be fentanyl, Ms. Glassnap said. The loss prompted her to seek treatment, and she said she remains in recovery. Her fiancé’s son died in 2020 after also taking what he thought was cocaine but really was fentanyl, she said. Afterward, she moved out of Columbus to Galion, a small city an hour and a half away, to escape the turmoil of drugs. She said she makes and sells jewelry and receives disability payments for past injuries.

Cierra Grambo, 27, who also grew up in the Bottoms, said she started using pain pills and sedatives when she was 18, then moved to heroin. She said she saw TV reports about how fentanyl was killing people and stayed away from the drug until one day in 2018 when it was the only drug she could find.

Ms. Grambo said her addiction progressed more rapidly than with heroin. Within two months, she was using up to $80 worth of fentanyl a day that she funded in part by stealing, compared with $20 a day she had previously spent on heroin, she said. Her tolerance climbed quickly as well, she said, to the point that she no longer used it to feel high but to avoid the sickness brought on by withdrawal. When she tried to get clean the withdrawals were worse than with heroin, she said, including once at a treatment center in 2019.

“I was literally ripping my hair out,” said Ms. Grambo, who recently completed residential treatment at Maryhaven and continues in recovery. “Every time I took a breath, it felt like something was ripping in my stomach…I wanted to die.”

What she experienced is known as precipitated withdrawal, she said, a sudden, severe condition that can occur when a user hasn’t sufficiently come down from opioids before being administered Suboxone, a medication that combines buprenorphine, used to treat opioid addiction, and naloxone. The number of users at risk of precipitated withdrawal at Maryhaven has increased in recent years because they are arriving with such high levels of fentanyl in their bodies, said Mike Gersz, Maryhaven’s director of outpatient services. “They’re much sicker, with much higher acuity, and more difficult to treat,” he said.

Write to Arian Campo-Flores at arian.campo-flores@wsj.com and Jon Kamp at jon.kamp@wsj.com